I’ve never taken to Kafka’s existential fiction. I can at least say I’ve not forgotten the opening scene of a salesman waking up one morning transformed into an insect. A cockroach, to be specific, according to some adaptations of Kafka’s modern classic. It’s pretty unforgettable, as literary scenes go.

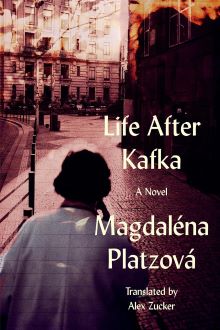

Last year I read 1913: The Year Before the Storm, a nonfiction book that mentions Kafka’s relationship with fiancée Felice Bauer. He was torturously undecided about his commitment to their love. A new novel about Felice, Life After Kafka, consequently drew my attention. It’s been more than a month since I finished it, and yet it has stayed with me in scenes concerning this invisible woman whom Kafka scholars haven’t touched. Also, author Magdaléna Platzová shares her research experiences in some chapters, and that’s fascinating. One of Felice’s great-grandsons, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas, becomes her link to the family.

We first meet Felice in Geneva 1935 with her husband and children. Having fled Hitler’s Berlin, they’re now preparing to emigrate to America. The breakup with Kafka is long in the past. She was engaged to him for five years (1912-1917), when he drudged away by day at an insurance company in Prague. At night he wrote his famous stories and also more than 500 letters to Felice in Berlin. She saved his letters, but her letters vanished. (It’s speculated she asked Kafka to return them when she last saw him, and destroyed them.) In Geneva, her friend Grete Bloch arrives for a surprise visit on her way to Tel Aviv. Grete is a major figure in Felice and Kafka’s history, notably as a negotiator during their difficulties, and the rumor Kafka might have fathered a child with Grete.

Next Felice is in Paris, 1938. She arrives from Los Angeles, which is now her family’s permanent home. Her husband is in a Paris hospital, having suffered a heart attack on a business trip. A successful financial executive in Berlin before the war, he had hoped to revive relations with clients looking for safe, profitable American investments. The heart attack ends that hope. While in Paris, Felice visits a former work colleague she knew in Berlin, a man who once accused her of refusing to help Kafka when he struggled with writing, the job, and finances. She gives the man a packaet of money, this Jewish man who now has lost everything, but not before asking him:

Why did you meddle in our affairs? Why did you talk him out of the wedding?

Back in Los Angeles, Felice’s fragile husband is confined to an armchair, unable to work. She becomes his caretaker and supports the family with beauty, baking, and knitting businesses. She rarely gives Kafka a thought — he died in 1924 of tuberculosis — and she keeps her past a secret with the family. Until a biography of Kafka, written by his childhood best friend and literary executor, Max Brod, has been published, and she’s in it.

Chapters jump back and forth in years and places. Some are dedicated to Grete Bloch, who didn’t survive the war, and also to Felice’s adult son, who describes her as a warm, generous person and “a woman of many talents.” The fragmented approach challenges a chronological narrative flow, and yet it works. Rather than attempt to illustrate lifelong details, Platzová excavates the gems and drops them into a context of her examining questions and discoveries. There’s an integrity of purpose here that makes Life After Kafka more grounded in actuality than something purely speculated.

After the war, New York 1946, everyone is reading books by Franz Kafka. Felice’s son, a child psychologist in the city, watches college students reading The Trial and The Castle on the subway. There’s something haunting in this image – the son knowing his mother was once engaged to Kafka but not knowing the details of their relationship, or what Kafka meant to her. He knows she has kept Kafka’s letters. He pressures his mother to sell them to an insistent New York publisher. “As if she should trust them with the letters,” we read, her struggle heartbreaking.

Life After Kafka is a bold exploration of exile, literary history, and the price paid for being part of it. In an interview at his retirement home, Felice’s son tells Magdaléna Platzová that his mother, in poor health, needed the money the letters would bring. Also, if he hadn’t convinced her to sell them, she would’ve burned them. The letters were first published in Germany in 1967. It was a literary event.

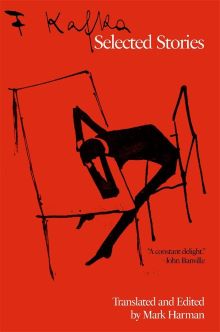

Reading Life After Kafka (translated by Alex Zucker) led me to Selected Kafka Stories, a new book translated and edited by Mark Harmon. The book includes a 67-page biographical introduction, which filled out Kafka’s life for me. I also like how Mark Harman introduces each story with informative insights, putting them in context with Kafka’s life. For example, “The Metamorphasis,” the story about the bug originally titled “The Transformation,” was written in three weeks in 1912.

According to Kafka, the idea for ‘The Transformation’ occurred to him during the first serious crisis in his mostly epistolary relationship with Felice Bauer as he lay despondent in bed, having decided not to get up until he received a long-awaited letter from her.

While reading Life After Kafka, I wondered if knowing something about Kafka’s life mattered to the story. That’s why I picked up Mr. Harman’s book. Ultimately, I don’t think it’s necessary. I think for me it was the curiosity Magdaléna Platzová’s book sparked, creating a want to know more about Franz Kafka (1883-1924) and his work, leading me to another book. It’s what books do, this thread they can create, guiding us to other books and stories we otherwise might miss.

A version of this review of Life After Kafka aired on NPR member station WOSU 89.7 FM broadcasting throughout Central Ohio.

I enjoyed your narrative. You are, of course, a part of the “thread” that you describe so eloquently.

LikeLiked by 1 person