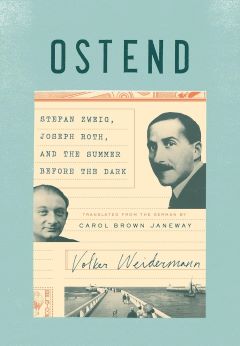

I’ve been meaning to read Joseph Roth’s The Radetzky March ever since I learned about Roth in Volker Weidermann’s excellent book Ostend: Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, and the Summer Before the Dark. My self-imposed need to have the edition translated by Michael Hofmann caused some delay – Hofmann is one of the world’s most important translators of books from German to English, especially Roth literature. Of note: He’s the translator of Kairos, which won this year’s International Booker Prize, a novel by German author Jenny Erpenbeck. When the Hofmann edition of The Radetzky March finally arrived, it sat on my TBR table for some time.

Oh what a mistake I made waiting! This historic fiction is tremendously good storytelling, rich with incident, melancholy, and family legend. First and foremost, The Radetzky March is about the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. It follows three generations of the Trotta family through the lives of a grandfather, son, and grandson, each connected to serving the Monarchy of Emperor Franz Joseph. But it’s also about belonging and identity.

Joseph Roth was born in the extreme east of the Habsburg Empire in 1884. He spent time with the Austro-Hungarian Army on the Eastern Front in World War I. From a biography I found in his novels in my library, he’s quoted as having written:

My strongest experience was the War and the destruction of my fatherland, the only one I ever had, the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy.

The story begins with the Battle of Soferino in 1859. A young Lieutenant Trotta saves the life of the Emperor when His Majesty lifts an eyeglass to observe the battlefield during a pause in the fighting. He doesn’t realize his gesture is a common sniper’s target. Trotta throws himself at the imperial ruler, pushing him to safety, and taking a bullet. He’s immediately promoted to captain and given the title of baron.

Captain Trotta becomes uncomfortable over time with his exaggerated, heroic legacy. He has peasant roots, and longs for the simplicity and honesty of those roots. His son becomes a District Commissioner, a provincial official loyal to the emperor. He too has a son, Carl Joseph, who becomes a cadet and then a lieutenant, but like his grandfather, struggles to uphold the family legacy. His instability takes root in the misperception of an affair that causes the senseless death of his only friend.

Out of the whistling emptiness in his head, a thin, weaselly sentence strings itself together. The Lieutenant clacks his heels together (from soldierly instinct, and also in order to hear some, any kind of noise), and the jingle of his spurs solaces him. Then, very quietly, he says: ‘There’s nothing going on between your wife and me, Regimental Doctor!

The good years under Franz Joseph’s reign weaken at the seams in the early 1900s. Roth rarely mentions dates, but cleverly manages time through his aging characters, such as the death of a Trotta manservant, long ago hired by the late grandfather. He dies of old age in the service of the Commissioner, now an old man himself, symbolic of the dying empire. Incidents energize the forward movement of the narrative, while descriptions of setting, mood, place, and time, let alone despair, yearning, indifference, and awkwardness, make everything and everyone visible to us.

“And now [the District Commissioner] was leaving there lonely, leaving his lonely son, leaving this frontier, where the end of the world could clearly be seen coming, as one might see a storm brewing over the edge of a city, while its streets are still basking innocently under a cloudless sky.”

Joseph Roth published The Radetszky March in 1932. When Hitler rose to power, Roth emigrated to Paris. This Jewish author’s books were banned by Nazi Germany. Roth died in Paris in 1939. He was moneyless and alcoholic, leading an unheroic life, enormously vulnerable, and dependent financially on his friend and fellow author Stefan Zweig. Ostend by Volker Weidermann, mentioned earlier, captures their friendship, their exile, and a historically impactful time for Roth.

Roth’s novel is immensely gratifying by the way it brings to life the Trottas’ duty and loyalty to their fatherland, and the sorrow and longing that arrives as the empire vanishes. The signs of collapse seep into the story through events, but also Carl Joseph’s personal traumas and his father’s struggle to help his son, while staying true to his pride and identity. What Roth felt himself during these years of decline likely contribute to what make this novel a masterpiece. There’s no other way the prose could be written with such deeply felt understanding.

In the years before the Great War, at the time the events chronicled in these pages took place, it was not yet a matter of indifference whether a man lived or died. When someone was expunged from the lists of the living, someone else did not immediately step up to take his place, but a gap was left to show where he had been, and those who knew the man who had died or disappeared, well or even less well, fell silent whenever they saw the gap. … That’s how it was then! Everything that grew took long to grow; and everything that ended took a long time to be forgotten. Everything that existed left behind traces of itself, and people then lived by their memories, just as we nowadays live by our capacity to forget, quickly and comprehensively.

Saving the honor of the House of Trotta and the difficult realities that must be faced loom large for the District Commissioner Franz Baron von Trotta. As the pages we read become fewer and fewer, we know what’s coming. It’s inevitable, if you remember your history, the assassination in Sarajevo of the Habsburg heir to the throne, which sparks the beginning of World War I. For Franz Baron von Trotta, son of the hero of Solferino, “His world had ended.”