Small print on the copyright page of The Photographer at Sixteen states this remarkable memoir by British poet and translator George Szirtes is a work of fiction. In other words, memory is unreliable. Szirtes fully acknowledges that unreliability in this transfixing remembrance of his mother, Magda Szirtes, who died July 31, 1975, at the age of 51 from a suicidal overdose.

Her oldest son writes not out of biographical precision, rather out of a need to know the what of her past and the why of her adult, maternal years, working with photographs, letters, family conversations and his own vague memory. At one point he writes, “I am imagining this.” At another, he writes, “I have no image of her from that period so must guess at some composite of earlier and late photographs.” And at another, “How can five entire years vanish into such dense fog? Let me recall what I can.”

Szirtes’ honesty — that claim to imperfection and to leaning on imagined possibility — is refreshing for its faithful openness. We all remember like this, at once truthful and sketchy, and such a genuine approach reaches out to readers with a personal, warm tone. It draws us authentically close.

Reaching Toward the Unwounded Beginning

There’s something else that raises this memoir above the common pool of personal history — Szirtes writes his mother’s story backwards, beginning with the suicide and ending with her childhood in Transylvania. In between, Magda survived internment at two concentration camps during WWII — two months in Ravensbrück and then three months in Penig, until the Americans arrived.

The reversal is a powerful, impressive technique, at first unsettling for Magda’s pervasive dark moods burdening her husband and two sons. At the beginning, these moods are without explanatory history for us. They are followed in the turned pages by her alluring and mesmerizing beauty and personality, as Szirtes takes us backward into prior years. His inspiration for this construct comes from Anthony Hecht’s poem “The Venetian Vespers,” in which Hecht describes a diver returning feet first from the pool to the diving board. Szirtes writes,

Moving backwards may be like healing a wound, returning to a perfect unwounded beginning where all is innocence and potential.

From England Back to Hungary

The Szirtes family arrived penniless in London, refugees from the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. They rebuilt their lives with renewed success that provided houses and material wealth. In the last house, where Magda took her life, her unhappiness, exhaustion and failing health from a heart condition oppressively dominated the atmosphere. She transferred her desperation for a hopeful future onto her sons, expecting them through hours of study and practice to become a doctor and violinist.

Even as I write of the memoir’s scenes, there’s an odd feeling, like walking backwards with eyesight facing forward. You have to make a conscious adjustment with your footsteps, your thinking, so you don’t fall over or get dizzy. One into the flow of the narrative, nothing like that happens, as the author, a talented, award-winning poet, deftly manages the rhythm of the receding tide, keeping us steady with cues of time and place.

As refugees in flight, László and Magda had planned to settle in Australia, where László had family and a promised job. The refugee quota for Australia, however, had been met, so the family traveled to England as a means to eventually get to Australia, except Magda’s application was denied for medical reasons, her weak heart. This was the moment suicidal thoughts began. She blamed herself for this further loss, and she encouraged her husband and sons to go to Australia without her.

From Ravensbrück Back to Childhood

Szirtes cannot rebuild Magda’s experience in the concentration camps. Nevertheless, he crafts an involving narrative that attempts to know what it could’ve been, and to understand what she felt. Also, he knows little of her recovery after liberation, including the story of an American soldier (George) who asked Magda to marry him.

I cannot explain Magda by Ravensbrück or Penig. I cannot define her in such exclusive terms. She had had twenty years of life before and had thirty years after. However terrible the experience of the camps they weren’t the only events of her life, nor indeed of any other survivor’s life. In each case it was a whole person who went in and a whole person who came out, it’s just that the relation between the two had changed.

Szirtes takes us out of WWII to before this horror, when Magda pursued photography as an apprentice to a master in Budapest. This was the beginning of the great age of magazine photography, he tells us, but it was also the time of Hitler’s ramp-up in racial hatred and war, putting Magda’s Jewish life in danger. When she was 16 years old, Magda met 23-year-old László. Prior to that, at age 14, she developed rheumatic fever, the precursor to her heart trouble, and dropped out of school. All this time, she did not know what we now know, that she would survive two concentration camps, be turned down for a better life in Australia because of her weak heart, and raise two sons, the one she wanted to be a doctor instead becoming a poet who would write this book.

The further away Szirtes gets from Magada’s adult life and into her childhood, the less he knows.

The tide is sweeping her away from me.

Still, George Szirtes, her oldest son, doesn’t give up, delving in to learn of her father – his grandfather — who deserted the family when Magda was four years old. There are records of him as a stowaway in 1928 on the S. S. Patagonia crossing the Atlantic from Antwerp to New York. He returned but disappeared again without record of what happened to him. Szirtes knows little about Magda’s handsome brother. Her family died in the Holocaust.

The Diver Returns

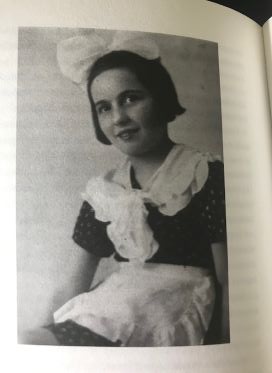

Szirtes focuses on five photographs to conclude the book, including the one used on the front cover. Another one shows a childhood photo of Magda wearing a white Minnie Mouse bow in her hair. Szirtes estimates she was 12 or 13 years old.

On the book’s last page, Szirtes writes:

I don’t have a photograph of my mother as a new-born child so I can’t position her first appearance in life on the very top of the diving board.

But he does bring us into the innocence and hope of the beginning, before the furious fates take their toll to create an exhausted, demanding woman who took her own life. The water is sparkling and clear.

The Photographer at Sixteen is published by Maclehose Press in London.

Thanks for bringing this book to my attention, Kassie. Definitely going to read this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad to hear this! You’ll likely need to buy it, as U.S. publishers haven’t picked it up yet. In other words, libraries won’t have it. But it’s a reasonable price from the Book Depository, which you can access via Amazon. I hope you enjoy it.

LikeLike